On March 10, 1991, in the Penta Hotel, an ever-dwindling New York City crowd had just sat through twenty-two wrestling matches of varying quality. The television taping they attended started late, was running long, and fans had left in droves. Considering there were only 400 people in attendance when the night started, Herb Abrams, owner of the just-launched Universal Wrestling Federation (UWF), could not afford to lose a single person, much less droves.

Abrams grabbed a microphone at ringside and implored the ambivalent masses to stay for one more match, the main event. Several fans took pity on the man and returned to their seats. Others ignored the request entirely and made their way to the exit. A few seconds later, “Soul Man” by the legendary R&B duo Sam & Dave began playing over the P.A. and Antiguan pro wrestler S.D. Jones emerged from the curtain (Mr. Haiti in tow). Almost immediately, many fans still in attendance collected their things and headed for the door. Roughly 30 seconds later, Herb Abrams did the very same thing — arguably the first and last time Herb Abrams made the right decision during his five years as head of the UWF.

Thanks to generous financing from “Nigerian investors” (yeah, that sounds legitimate), Herb Abrams’ Universal Wrestling Federation (not to be confused with Bill Watts’ promotion of the same trademark-less name) got up and running in August of 1990 after he secured a television slot on SportsChannel America (which found itself in need of pro wrestling programming after dropping the much-maligned IWA). Abrams boasted a stacked roster of legendary pro wrestling names like Terry Funk, Big John Studd, and Ricky “The Dragon” Steamboat, and traded on their star power to seal the deal with the channel. Granted, none of these men had agreed to wrestle for the new promotion, but Abrams knew enough to never let the truth get in the way of a perfect lie.

After a press conference that included “Dangerous” Danny Spivey and B. Brian Blair, the UWF taped episodes of Fury Hour in September of 1990 in Reseda, California, while simultaneously attempting to put on live events. Abrams had pieced together a roster filled with former stars, but by 1990, Bob Orton, Jr., “Mr. 1derful” Paul Orndorff, and Billy Jack Haynes didn’t carry the same drawing power in the U.S. as they had a few years prior.

Abrams also hired Bruno Sammartino, but considering the longtime (W)WWF Champion had retired from in-ring competition, what he got was one of the worst commentators of all time rather than one of the greatest wrestlers ever. Bruno’s son, David, was also signed. Unfortunately, for fans, he did wrestle for the company.

Purported UWF booker, Blackjack Mulligan, wasn’t even aware he’d been hired (you know, what with him being in jail at the time for counterfeiting and all). Abrams had a backup plan — an expressed interest in bringing Bruiser Brody on board for the position — the same Bruiser Brody who died two years prior. Ultimately, the owner named himself as UWF’s booker.

Things were off to a roaring start for Herb Abrams.

With a roster loaded with known quantities, albeit ones looking for a payday more than a platform to showcase their skills, that didn’t leave much room (or money) for young guys trying to make names for themselves. With one of the few remaining spots amid the sea of grizzled veterans, Abrams hired a blonde-haired, 20-something former bodyguard for Hulk Hogan named Steve “Wild Thing” Ray.

Ray started in pro wrestling in late 1987, working throughout the Midwest and competing for a few regional championships in Kansas and Missouri. The 6’3” former football player had a good look and plenty of desire, but the UWF started in disarray (and only got worse as time passed).

By May of 1991, a supposed divide between Abrams and Ray had grown into a chasm, leading to one of the weirder stories in UWF’s short history. Abrams suspected his wife of having an affair with Ray and paid Steve Williams, a former standout football and wrestling star at the University of Oklahoma (and a multi-time, multi-promotional pro wrestling champion), an extra $100 to break the young wrestler’s nose during a match. When you ask a guy nicknamed “Dr. Death” to hurt someone, you typically get what you pay for. After being thrown around for several minutes, Ray turned his attention to Abrams, who had climbed into the ring. Ray unleashed a wild swing at the UWF owner, but Abrams ducked it and made his escape.

The question is, was this a shoot? Steve Ray has said it was all set up by Abrams to garner some heat and that he owes a lot to his former boss for showing him the “dos and don’ts” of running a successful business. Former UWF vice president Zoogz Rift disagrees with Ray, claims that Abrams’ anger was real, and says, “Ray allegedly screwed Herb in a drug deal”. Ray stands by his account, pointing to the end of the match, where you can see Abrams whisper something to the wrestler (presumably telling him to take a swing at him). Ah, yes, the joys of pro wrestling mythology!

On June 9, 1991, the UWF held its first (and only) pay-per-view. Beach Brawl at the Manatee Civic Center in Palmetto, Florida, took place before 550 mostly indifferent people. The PPV started on the wrong foot when the opening bout, a Street Fight between Terry “Bam Bam” Gordy and Johnny Ace, supposedly ran long, which threw the rest of the show into upheaval.

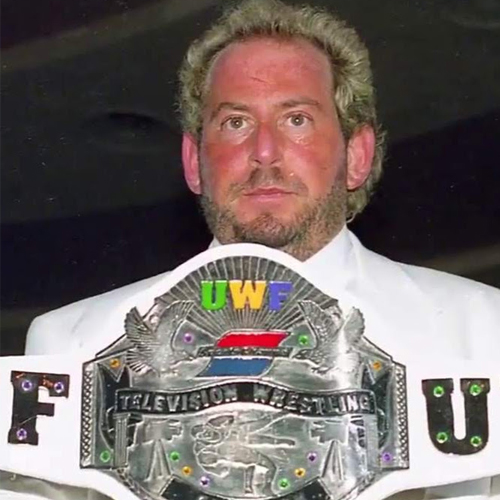

The main event was a match between Steve Williams and Bam Bam Bigelow to crown the UWF Television Champion. Williams won the match, but no one really won a thing that night — with a buy rate of 0.1, Beach Brawl set a record for the least purchased PPV in wrestling history.

The norm for the fledgling promotion became canceled events and poor attendance, often due to incompetence on the part of Abrams (or unrealistic expectations from SportsChannel). Credit to the owner for hustling every step of the way, but as Zoogz Rift said, “Money was always around, but he (Abrams) spent it in the wrong places”. Wrestling finishes often made no sense, a product of Abrams’ lack of experience as a booker (coupled with a veteran roster that had little respect for him). Rift, who took over booking the promotion for a time in 1993 and 1994, left, then returned to serve as vice president of the UWF until Abrams died in 1996, believes the company failed because Abrams was “more interested in feeding his drug addictions”.

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearlyBetween 1994 and 1996, Abrams made several plans to relaunch the UWF. Unfortunately, according to Rift, the money “always went up Herb’s nose”. The UWF filmed wrestling events in North Dakota and Minnesota but never released them. ESPN2 licensed existing television episodes, and Abrams sold exclusive rights to the UWF catalog to several international companies. You read that correctly — he sold exclusive rights to multiple companies. Ultimately, no real momentum was achieved (where a relaunch was concerned, at least).

Herb Abrams’ “final stand” took place on July 23rd, 1996 in the very same part of the world where, just five years prior, he begged a disinterested audience to stay to the end of a UWF TV taping. Having already been arrested in five states and awaiting trial on several charges, including attempted rape, robbery, and drug possession, Abrams was confronted by police in his Manhattan office space after a reported disturbance. There, police discovered “Mr. Electricity” naked, covered in Vaseline and cocaine, and chasing two prostitutes around with a baseball bat. Abrams had destroyed several pieces of furniture and was quite unwell.

Police took him into custody and headed to the nearest hospital where, an hour and a half later, he had a massive heart attack due to a cocaine overdose. Herb Abrams died instantly.

Herb Abrams’ UWF legacy is far more ‘haha’ than ‘holy shit’, but he does deserve credit for creating something that WWE and WCW would later employ to massive rating spikes: Abrams was the first authority figure heel in pro wrestling. Vince McMahon and Eric Bischoff made themselves evil bosses on RAW and Nitro during the white-hot “Attitude Era” — Herb Abrams beat them to the idea by five years (albeit with far less success). Still, the man deserves a doff of the cap for being ahead of the game.

Abrams also deserves recognition for being a fan who went all in and tried to put out the kind of product he wanted to see. It was usually awful, but it was his to have and hold. He had zero experience to draw upon, but props to him for at least trying. In that way, he differentiated himself from the standard complaining wrestling fan, content to sit and whine.

Leave a comment